Australia’s decision makers have decided to give us nanotechnology whether or not we want it, and anyone wishing to avoid participating in this experiment needs to keep asking questions. Martin Oliver reports.

In every era, a new frontier is explored. A few decades ago, the space program stood at the cutting edge. Today, this has been replaced by the science of nanotechnology, with the infinitely small taking the place of infinite distance. Some futurists believe that this field of discovery will in time immeasurably improve our lives.

But what lies behind such techno-optimism? Is technology really capable of solving all our problems? There seems to be a gulf between the wide-eyed prophets and the average person on the street, who is liable to view new science with bemusement, indifference or some concern about the potential risks and dangers.

In his 1986 book on nanotechnology, Engines of Creation, US engineer Eric Drexler proposed a nightmare scenario in which human-created nano-machines self-replicated out of control, turning all life on the planet into an homogenous “grey goo”. Although this type of fear has abated from the nano-debate, Drexler characterised nanotechnology as an area of enormous potential benefits and extreme risks.

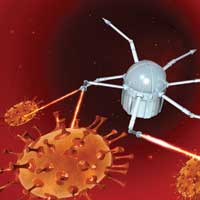

One fringe nano-subculture is looking at breakthroughs that may enable us to “nano-ise” the human body, creating a hyper-intelligent superhuman or human-robot cyborg. This field of transhumanism is attracting adherents.

Origins of nanotechnology

The conceptual basis for nanotechnology was established in 1959 by the American physicist Richard Feynman, who first proposed the radical manipulation of atoms and molecules in a seminal talk entitled There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom. Later, in 1974, Japanese scientist Norio Taniguchi coined the term “nanotechnology” to describe such an activity. Research began during the 1980s, and developments have since gathered pace.

In 1985, the first nanoparticles were artificially produced in the laboratory. These particles, known as “fullerenes”, are engineered carbon molecules that can either be spherical (the buckyball) or cylindrical (the carbon nanotube). A typical nanoparticle is about one hundred thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair. Matter on the nano-scale normally measures less than one hundred nanometres, and a nanometre is one billionth of a metre.

Hollow like a football, the buckyball was named after the celebrated American inventor R. Buckminster Fuller, because of its structural similarity to his most famous discovery, the geodesic dome. The nanotube, made from a flat sheet of carbon rolled into a cylinder, was discovered in 1991. Recent research has been looking at linking nanotubes in series to produce “nanowires”, which could become central components in very small circuits of the future.

At the nano size, materials that have previously behaved predictably start to exhibit unusual properties that link them to the quantum realm. Colour, magnetism, and electrical conductivity change in unexpected ways, while strength and temperature tolerance are often greatly enhanced. Copper changes from opaque to transparent, aluminium becomes combustible, and gold turns into a liquid.

Nanoparticle exposure risks

As nanotechnology has spread from the laboratory into manufacturing facilities, concerns have been raised about potential risks to workers and the public.

Experimental results indicate that manufactured nanoparticles are more chemically reactive and toxic than their standard equivalents. This has led the UK’s Royal Society to state in a report that these particles should be treated as new chemicals, and subject to new safety assessments before approval.

{quotes}It has already been established that nanoparticles can enter the bloodstream and brain, and may cause lung damage and cardiovascular disease.{/quotes} A 2008 study where carbon nanotubes were introduced into the stomachs of mice showed asbestos-like disease profiles. In 2004, largemouth bass exposed to buckyballs in their water suffered brain damage. Cambridge University researchers have found that nanoparticles can penetrate the nucleus of a human cell, possibly damaging the DNA inside.

The consumer sector

The Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN), which is keeping a close eye on products that are known to contain nanoparticles, has a list of more than eight hundred items, with around three to four being added every week.

Types of nanoparticles that are already seeing commercial use include:

Titanium dioxide – in sunscreens, cosmetics and food product packaging.

Zinc oxide – in sunscreens, cosmetics, coatings, paints and varnishes.

Silver – as an antibacterial in products such as socks, cling wrap, refrigerators, washing machines, and toothpaste. Samsung has created a range of nanotech electrical appliances in a range that it named Nano Silver.

Like Samsung, some other companies wear the “nano” label as a badge to convey the impression that their offering lies on the cutting edge of technological innovation. Both the iPod and India’s car company Tata Motors each have a Nano on the market.

Without accurate labelling, consumers cannot make informed decisions about those products that have nanoparticles in them. For this reason, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) wants to see mandatory labelling of products that use nanotechnology. The same recommendation was also made in 2008 by a New South Wales parliamentary committee. Although the NSW Government responded by pushing for the national labelling of nanoparticles used in workplaces, it has stopped short of calling for consumer labelling.

Disclosure is optional

With the introduction of widespread labelling unlikely in the short term, dissenting consumers must research likely categories of nanotechnology products, phoning the companies involved about likely nanoparticle content, and asking for a written response. The PEN list is helpful, but far from exhaustive, being based on manufacturer-declared nanoparticle use in a commercial environment where disclosure is optional.

If an item is labelled with the selling point “antibacterial”, it indicates possible nanoparticle content. However, other non-nanotech antibacterial products may use chemicals that some people would prefer to avoid.

The inevitable by-product of manufacturing is disposal, and unless nanotechnology industries are reined in, an ever-increasing quantity of nanoparticles is likely to enter the environment, with unpredictable consequences. So far, government authorities appear to have been paying little attention to this issue.

Sunscreens and the TGA

As a class of product, sunscreens are perhaps more likely than any other to contain nanoparticles. The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), entrusted with regulating sunscreen products in Australia, stated in 2006 that 70% of the titanium dioxide used in Australian sunscreens and 30% of the zinc occurred in nanoparticle form. Conventional zinc has a white appearance, whereas nano-scale zinc appears clear on the skin, creating an obvious selling point.

Researchers from BlueScope Steel, a division of BHP, recently came across an unexpected problem with the company’s Colorbond roofs. Hand-shaped areas were identified where the roof steel was degrading about 100 times faster than expected. The culprit was found to be nanoparticle sunscreens used by workmen, and BlueScope has since put out a list of recommended non-nanoparticle brands.

{quotes} An Indian study from 2008 has shown that zinc oxide nanoparticles can damage the DNA in skin cells.{/quoted} But the TGA has declined to introduce any new nano-specific regulation or labelling requirements for sunscreens, and is unable to provide a list of nanotech products.

Fortunately this information deficit has been filled by Friends of the Earth (FoE), which has been campaigning on the nanotechnology issue for the past few years. One resource on its website is the Safe Sunscreen Guide, which provides a list of Australian sunscreen companies that have declared themselves nanoparticle-free. Some products are labelled as such on the packaging.

Nanofoods and packaging

Not content with exposing the public to nanoparticles in products, industry has recently started with minimal publicity to add them to our food and food packaging, where they serve as antibacterial agents.

This can be seen as one more in a series of contentious and unpopular adulterations to the food supply that include additives, irradiation and genetic modification. In 2008, a survey carried out for FoE found that 96% of Australians want safety testing for nanofoods, and 92% believe we should have labelling for nanofoods and nanotech food packaging.

According to a FoE estimate, up to 600 nanofood products have reached the global market, and it is likely that the food giants are researching others. Food types that may contain nanoparticles include bakery, dairy, fruit juices, soft drinks and cooking oil.

Choice magazine is calling for regulation of nanofoods, and a European Parliament committee supports mandatory risk assessments and labelling. These views are not shared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand, which contends that existing regulations are sufficient. It points out that food companies are required to provide information to the regulator about nanoparticle use, although these details are not available to consumers.

In the meantime, the best ways to be sure of avoiding nanofood are to buy unprocessed foods, or certified organic.

Lack of regulation

Is there a risk of falling in love with science to the extent that you cease taking a clear-sighted view? Have decision makers become so hypnotised by dollar signs that they are neglecting to apply the precautionary principle?

In the case of the genetic modification of food, with which nanotechnology shares some close similarities, a technology was initially allowed into the marketplace without public debate, labelling requirements or a regulatory framework. The Federal Government later adopted the contradictory position of being a keen proponent and regulator of GM food, and has distinguished itself by its unqualified support.

The ACTU has called for a range of precautionary measures in the nanotech industry, including steps to protect workers who may be exposed to nanoparticles on a daily basis. Lee Rhiannon of the NSW Greens has urged for a moratorium on nanotechnology products until there is adequate regulation, to protect human health and the environment.

To date, no country anywhere in the world has a nanotech regulatory framework in place, so Australia is not alone in that regard. But the common assertion made here that nanoparticles can be effectively regulated under the same rules as their non-nanotech equivalents goes against the scientific consensus. Â

Arguments advanced against nano-specific regulation include the notion that at present the industry is too little-understood for this to be effective: there is no straightforward protocol for identifying nanoparticle use. Other nanotech supporters are worried about the possible stifling of scientific research, and it can be guessed that many countries are scared to act unilaterally, with the risk of losing their share of the global pie in an industry that many people believe will soon be growing to vast proportions.

Resources:

Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies

www.nanotechproject.org

PEN consumer products list  Â

www.nanotechproject.org/inventories/consumer

Center for Responsible Nanotechnology

www.crnano.org

Friends of the Earth Nanotechnology Project

www.nano.foe.org.au

FoE Safe Sunscreen Guide

www.nano.foe.org.au/node/286